Hear Ye!

A year after discovering the joy of Russian literature, I attempted to translate Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella Notes from the Underground from Russian to English. It didn’t go super well. I don’t know Russian; I can pronounce most of the characters and know some words but that’s the extent of my expertise. After typing each word into Google Translate and finding its definition, I then took the individual translations and tried to piece the words together into something that could actually be read in English. (This is my idea of fun.)

The feel of the Russian text is what struck me most. The translation I had first read was by Constance Garnett, which conveyed some of Dostoevsky’s manic urgency, but only behind the veil of normal British manners. Russian itself is a much sparser language than English. It doesn’t use the verb ‘to be.’ Instead, it is implied. Articles like ‘a’ and ‘the’ aren’t used. There are far less prepositions. One of the most perplexing features of translation would be entering the word в and having Google tells me it means ‘in’, ‘to’, ‘at’, ‘on’, and ‘for’! Eventually, I just left it untranslated in my literal English version and proceeded to use whatever was the correct preposition in the final English translation. All this to say, in Russian, once stripped of all the fluff inherent to the English language, Dostoevsky comes across like a freight train.

This worried me about how we read all translated literature, but especially the Bible. What am I missing by reading the Bible in translation and not in the original Greek (New Testament) or Hebrew (Old Testament)? All my worries are conveniently captured in one word: “you.”

English is weird. Most languages will have more than one form of ‘you’, but in English ‘you’ is both the second person singular and second person plural, and there is no formal/informal distinction. Take Spanish for example. Spanish (in Spain) has ‘tu’ for informal second person singular, ‘vosotros’ for informal second person plural, ‘usted’ for formal second person singular, and ‘ustedes’ for formal second person plural. Latin American Spanish generally does drop ‘vosotros’ but still largely keeps the formal/informal distinction. Some languages don’t have this distinction (like Biblical Greek), but what is distinct about English is that we used to have a formal/informal distinction but we dropped it from the language. I think we should bring it back!

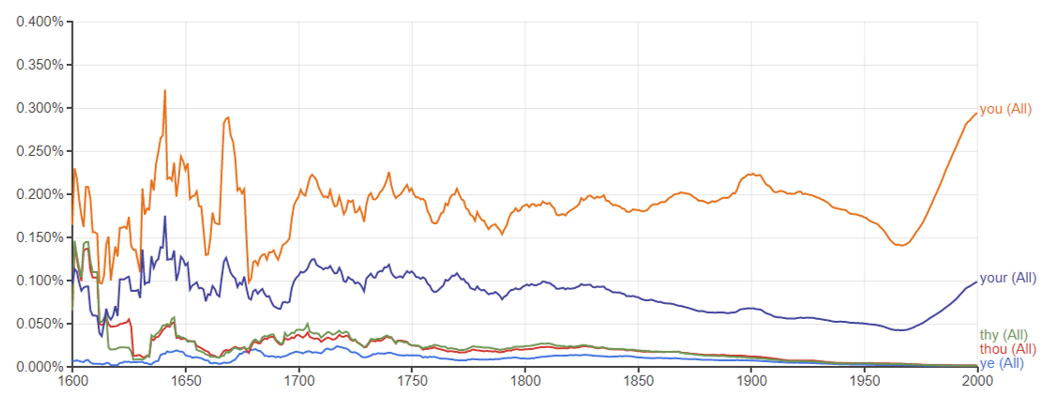

This chart shows the usage of ‘you’, ‘your’, ‘thou’, ‘thy’, and ‘ye’ from 1600 to 2000. Back in the day, ‘thou’ and ‘you’ functioned like ‘tu’ and ‘usted,’ respectively. ‘Thou’ was used for people you were close to, and ‘you’ was used for social superiors or strangers. ‘Thy’ is to ‘your’ as ‘thou’ is to ‘you’. ‘Ye’ was the term for second person plural, much like ‘y’all,’ ‘you guys,’ or (if you’re from Pittsburgh) ‘yinz.’ Think of the town cryer saying ‘hear ye, hear ye!’ This chart shows that at the turn of the 17th century ‘ye’, ‘thou’, and ‘thy’ were at their peak. And from 1604-1611 the definitive and longtime standard version of the English Bible, the King James Version (KJV), was being translated.

I worry that meaning and tone was lost from how we read the Bible in English when ‘ye’ and ‘thou’ were dropped. For example, Paul writing in Greek for his letters to the young churches will often us the plural form of you, which exists in Greek and in the KJV but not in modern English. This can easily lead to extremely self-centered readings of the Bible, where the individual is the focus and not the Church as a whole.

More than loss of meaning, I worry about loss of tone. As I mentioned earlier, there is no formal/informal distinction in Biblical Greek. Thus, the inclusion of ‘thou’ in the KJV is a deliberate choice to convey tone. Take for example the KJV Lord’s Prayer (or Our Father)

Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.

And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil: For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.

The translators use ‘thy’ and ‘thine’ intentionally to indicate the intimacy of the relationship between God and us. The language demonstrates that God is a friend that sticks closer than a brother, that the Kingdom of Heaven is near.

‘Thy’ and ‘thou’ are often cited as examples of Biblical language and the Church being old, stuffy, and out of touch. Because the KJV is the only place where ‘thou’ and ‘thy’ exist in modern English they have taken on their opposite meaning. ‘Thou’ is used to indicate closeness but it strikes our ears as distancing. We typically understand ‘thou’ as meaning that God is so far above us as to be incomprehensible, while the intention is to show that God humbles himself for us.

So let’s start using ‘ye,’ ‘thee,’ and ‘thou’ again. It’ll be weird at first, but the pros outweigh the cons. First of all, ‘ye’ is immensely practical. ‘Ye’ is the second person plural that we’ve been searching for this whole time. It doesn't have the negative associations of ‘y’all’. It doesn’t have the genderedness of ‘you guys’. It is much shorter than ‘you all’. And it’s not as hyper regionalized (or hideous) as ‘yinz.’ #BringBackYe.

Finally, while opening what I’m sure would be a messy can of social worms, using ‘thou’ and ‘ye’ would give us more insight into our relationship with God. ‘How great thou art’ has amazing poetical resonance by juxtaposing the greatness of God with our intimate relationship with him. This is the mystery and wonder of God that perhaps we lack the means to convey in modern English.

If ‘thou’ and ‘ye’ can fall out of the language, we can bring them back. These forgotten forms of you give the English language greater specificity and greater depth. I anticipate a long, tumultuous struggle, but I hope ye will join me!