Sacred Texts

I don’t really like articles with the premise that something interesting happened on Twitter this week. Alas, as so often in our tragic lives, we're doomed to become the things we hate. But, bare with me, because something interesting really did happen on Twitter this week.

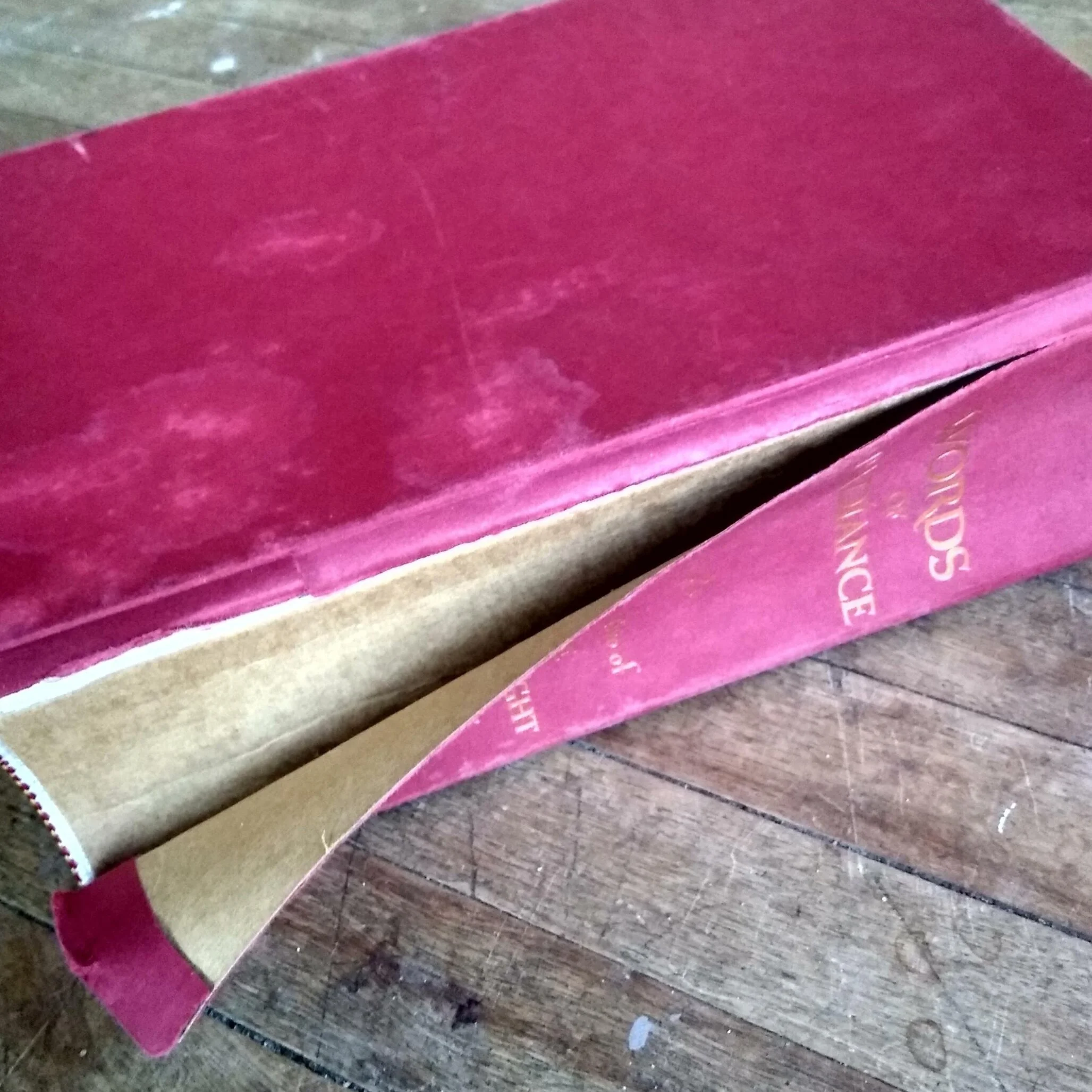

This Vox article has more details, but writer Alex Christofi tweeted that he cuts his books in half (vertically down the middle of the spine) to make them more portable, catalyzing the intense response on Twitter. These reactions reminded me of moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s truly exceptional book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. I can’t recommend it enough. In his book, Haidt gets to the heart of the real and seemingly growing divides in our culture. Haidt breaks down morality onto five different pillars: care/harm, fairness or proportionality/cheating, loyalty or ingroup/betrayal, authority or respect/subversion, and sanctity or purity/degradation. A person's morality is some combination of these pillars, and divisions arise because not everyone has the same combination of moral pillars.

As shown in the article I linked above, American liberals and conservatives consider different pillars in their moral decision making. On average, Liberals base their morality on two pillars, care/harm and fairness/cheating, while conservatives base their morality on all five. You can see the divides play out, for example, in Colin Kaepernick kneeling for the national anthem. For liberals, this is a noble effort to bring attention to the unfairness faced by minority communities in America. For conservatives, it’s a betrayal of the country and disrespectful to the people that fought and died for it. Or in the debate over abortion. For liberals, it is about fairness for women. For conservatives, it is about the sanctity of life.

I love the reactions to Christofi’s ‘book psychopathy’ because it runs into a moral foundation people didn’t know they had: sanctity/degradation. Vox sums up the reactions on Twitter (whose users tend more liberal): “Logically, they said, they could understand that it was fine for Christofi to do whatever he wanted to do with his own books. But emotionally, it was hard to look at books that had been cut in half.” So, logically, people on Twitter are thinking from a care/harm framework that someone cutting their own books in half doesn’t hurt anyone, but, at the same time, grappling with the emotional reality, which falls outside of their moral framework. Seeing books cut in half feels like an attack on something sacred.

Vox argues that it’s fine to cut books in half. The sacredness that we feel for books is merely a marketing ploy to get us to buy more books. I think this is too cynical a take. Bookishness may be a marketing ploy, but books are sacred, in a real sense, because of how we interact with them. I have many books and love them to probably too great an extent. While I don’t lose sleep over much, I have lost sleep worrying that mice will chew through my walls and destroy my precious books. My moral framework is also a little unusual; I consider three pillars: care/harm, fairness/cheating, and sacred/degradation. So my forthcoming defense for the sacredness of books may be, as Haidt would argue, merely a post ad hoc justification for my pre-existing moral intuitions, but nevertheless, books are sacred because they are part of us.

When I go to someone’s house, I almost immediately, almost rudely, stare at their bookshelf. People often say that certain objects ‘tell the story of your life,’ and by seeing what books a person has read or displayed, I get a sense of what they like and how they think. However, I think books go further than that. Books, especially owning and displaying books, are the embodied intersection of the mind of the reader and the mind of the author.

There’s a theory of cognitive science called distributed mind. It argues that while the brain is confined to a single individual, the mind of that individual is distributed through social relationships, culture, and objects. One of the simplest explanations people use for distributed mind is working out a math problem with paper and pencil. The paper is a sort of external memory which allows the brain to focus on the mathematical task without having to remember the steps that came before. The internet very often serves as an external memory, or that friend that knows trivia. Other people in my life (probably too often) serve as my memory for my schedule. Thus books, serve an extension of our minds, as a was struck by a quote in the Atlantic this week,

I know that either Rayner Heppenstall or possibly Richard Rees said of Orwell that he was too preoccupied with “the dirty handkerchief side of life”. But I find I must know exactly who said it and what the precise words were. Looking at my huge Orwell shelf I suddenly felt too exhausted to comb through it (which would once have been a pleasure) so I am employing you as a short cut.

Books, for authors, are a way to remember, innovate, and share themselves. For readers, books are ways to literally expand their minds and adapt themselves. The objects themselves are parts of the mind of both author and reader, and the overlapping humanity they contain venerate them into the realm of sacred objects. Cutting books in half profanes them by disregarding their power to share life with others, both living and dead.

To those who don’t love and cherish books like I do, this might be a stretch. But consider what the loss of old photos feels like. Or dropping your phone, or it running out of battery - dying. Not having your phone feels like losing part of yourself, because it is. It’s your memory, it’s your ear turned to the whole world, and your voice to both shout and whisper. Our phones, books, and, most importantly, people in our lives become part of ourselves, and losing them is the loss of something sacred.