The Shew Must Go On

Like lots of young men, I was resistant to reading Jane Austen. And of course by resistant, I mean absolutely opposed. Jane Austen was far too girly of an author for me to ever read, with all my hyper masculine pursuits like reading books and being in marching band. Fortunately, I realized the error of my ways when I watched the Keira Knightley version of Pride and Prejudice. It’s delightful and funny; Carey Mulligan and Keira Knightley are both in the movie, anticipating their amazing roles in Never Let Me Go. Anyway, reading the book a couple years later, I was struck by two things. First, that the book is everything the movie has going for it and more (except the actresses). Second, Jane Austen will write sentences like this, “... with an alacrity that shewed no doubt of their happiness,” spelling ‘show’ with an ‘e’ - ‘shew’.

As I talked about in the last installment of How Could You Be So Chartless, anytime there is a difference between British and American spellings of words you can generally attribute it to Noah Webster and his 1828 dictionary. Before 1828, nobody was spelling ‘colour’ without a ‘u’, nobody was spelling ‘centre’ as ‘center’. But his dictionary took off in America so we say ‘color’ and ‘center’ while the British (and Canadians) haven’t changed their spellings. But looking at the charts, ‘shew’ is different.

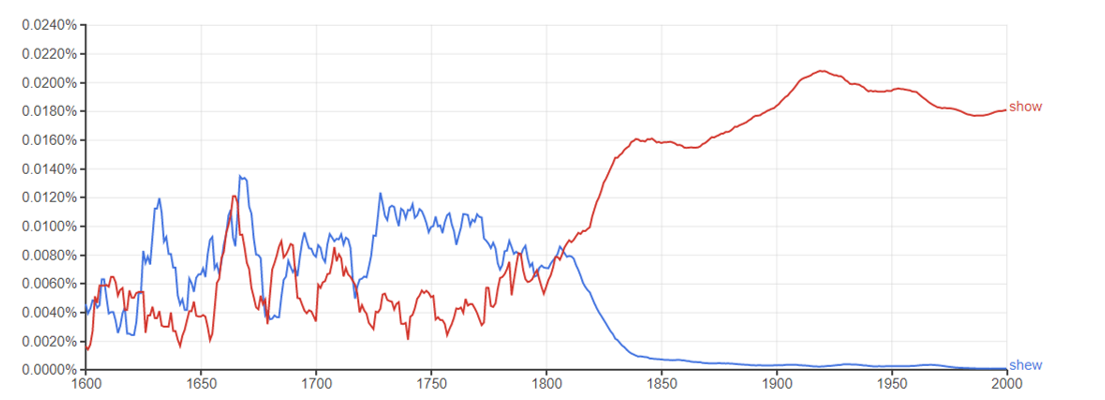

This plots the usage of ‘show’ in red and ‘shew’ in blue from the years 1600-2000. This looks kind of like the usage of ‘color’ and ‘colour’ in American English, but there are two key differences. First, the change in usage starts happening far before 1828, they start shifting around 1750 and they intersect in 1820, eight years before Noah Webster’s dictionary. Second, this chart is for British English. For Webster shifts, there’s no change in British spelling.

I have two possible theories for why this shift takes place and the theories are representative of two different views of history. One view of history, more prominent today, is like that espoused by Leo Tolstoy at the end of War and Peace. History, like change in language, is determined by the sum total of all actions taken by all individuals. Thus, events like wars and changes in government happen because of a large accumulation of causes. And this is how linguistic shifts usually take place, we can see that something has changed, but it can’t be traced to a definitive source, reason, or person.

My first theory, looking at the totality of events and their effect on the world, is about the Dutch. Many English words have roots in Germanic languages, including the word ‘show’. The Old English word is scēawian, meaning ‘to look at or inspect’, and the spelling ‘shew’ follows from the spelling of the Old English. However, after the Portuguese Empire collapsed, the Dutch Empire took over most of their holdings and became a trade power house. So the first theory is: as Dutch influence and language spread, their spelling schouwen shaped the English language.

Looking at what happens in American English could support this theory. The chart above shows ‘shew’ and ‘show’ from 1600-2000, but this time in American English. This is important because, before New York was known as New York, it was New Amsterdam. The Dutch controlled what is now New York City and the surrounding area before eventually losing it in a war with the British. If Dutch was influencing English, we would expect to see more and earlier use of ‘show’ in America than in England, and this is exactly what we see!

A second competing and long standing theory of history is “the Great Man” theory, where central figures (just a quick aside, it’s fun that we still spell central ‘central’ and not ‘centeral’), typically men, appear and radically change the global historical landscape. Think Jesus, or Napoleon, or Gandhi, or Hitler. It’s similar to the philosophy of the history of science that sees paradigm shifts. Someone like Newton establishes a paradigm, it goes well but eventually starts to build up questions, then Einstein comes along with special relativity and there is a paradigm shift. Or applying this to linguistics, “Great Men” like Noah Webster step in and cause a shift in language.

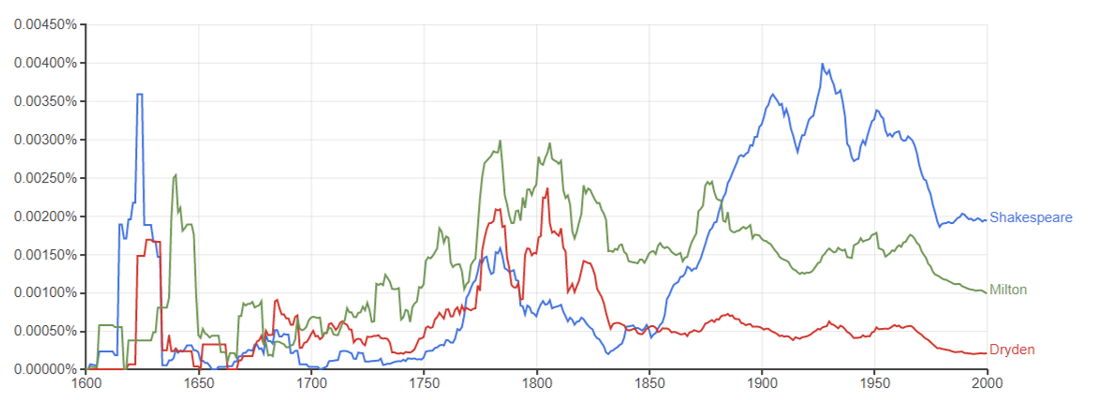

The second theory involves one of the quintessential “Great Men” of history, William Shakespeare (though people debate how much we know about Shakespeare, including if he was a man). Shakespeare was alive at the end of the 1500s through the beginning of the 1600s. When Shakespeare was writing, ‘shew’ was everywhere. The King James Bible, written contemporaneously, exclusively uses ‘shew’. For example, Genesis 12:1 “Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee.” John Milton, author of Paradise Lost who lived in the 1600s, exclusively uses ‘shew’. But Shakespeare and John Dryden, the other great poet of their time, are divergent. They use ‘show’.

Dryden is inconsistent. He uses ‘shew’ and ‘show’ almost interchangeably, while Shakespeare almost never uses ‘shew’. In all his works, Shakespeare uses ‘show’ 661 times and uses ‘shew’ three times. Two of those times are stage direction about “shewing someone a piece of paper.” Shakespeare is a crazy outlier for his time! Using mentions in books as a proxy for popularity, we see that Milton, Dryden, and Shakespeare all see peaks when they’re alive or recently dead. Their popularity fades, but later we see a renaissance of the poets at about the same time that ‘show’ begins to take off.

In all likelihood, the answer isn’t one or the other. The shift from ‘shew’ to ‘show’ is probably influenced by both factors, the increasing global prominence of the Dutch and reading the works of Shakespeare and Dryden. So reading Jane Austen and the King James Bible become like an archaeological dig, with ‘shew’ being the fossils of linguistic history. And this is why author and translator Mikhail Shishkin says that no word can truly be translated, because each comes not just with a meaning but a history.